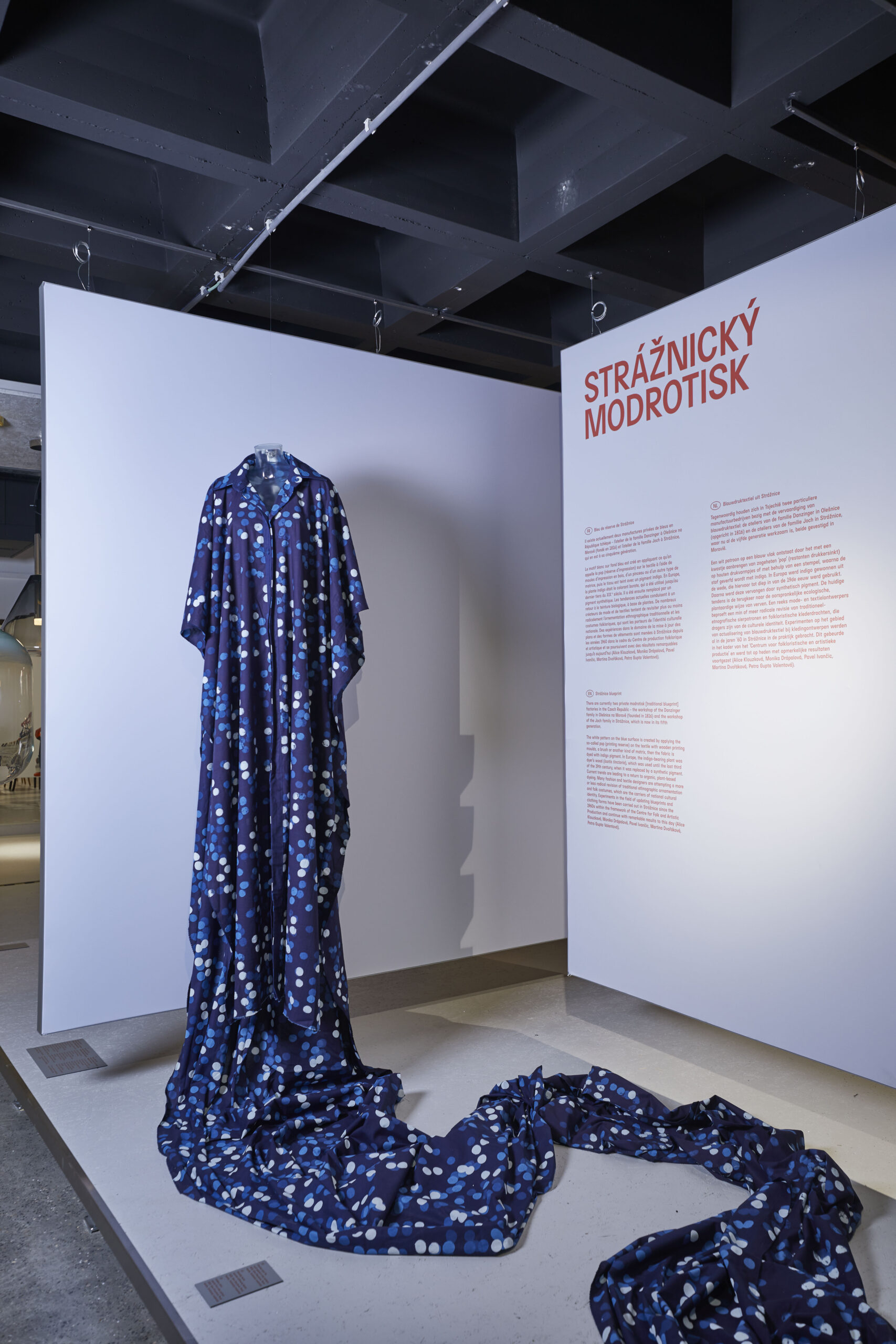

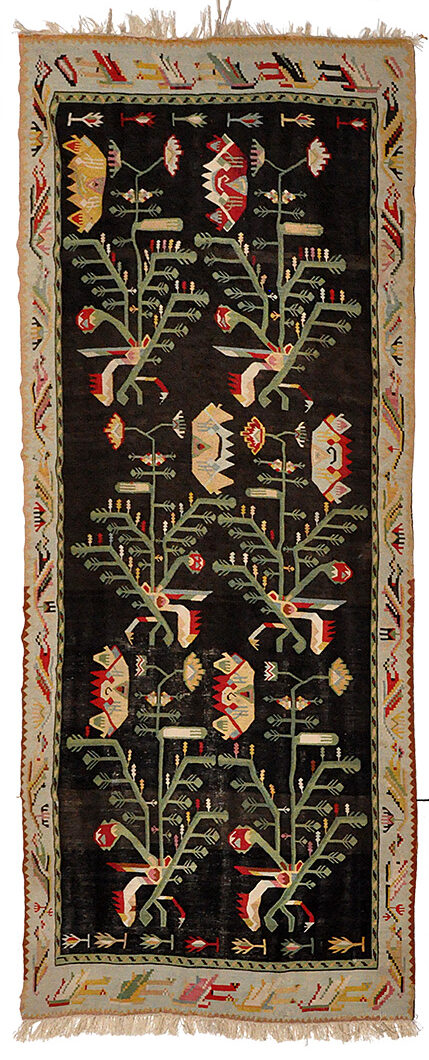

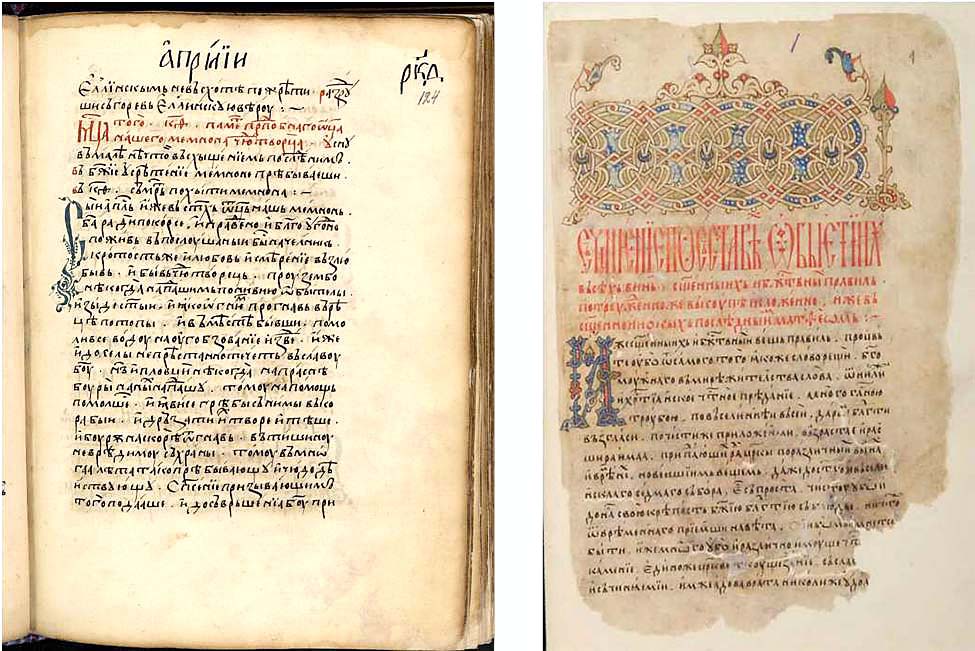

In the capacity of the Serbian Presidency of the Central European Initiative (CEI) in 2025, the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia invited the CEI Member States to give their contribution to the cultural presentation of the CEI Region in the field of Intangible cultural heritage, showing the traditional cultural elements from their countries that came to life on utilitarian objects, in order to show the whole spectrum and richness of the living cultural tradition of the CEI Region – through a digital exhibition showing the liaisons of the intangible heritage and industrial design and thus, representing the elements of the traditional cultural heritage of the CEI Member States.

The valuable and authentic contributions have been submitted by the following countries (13): Albania, Bosnia and Herezegovina, Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Serbia.

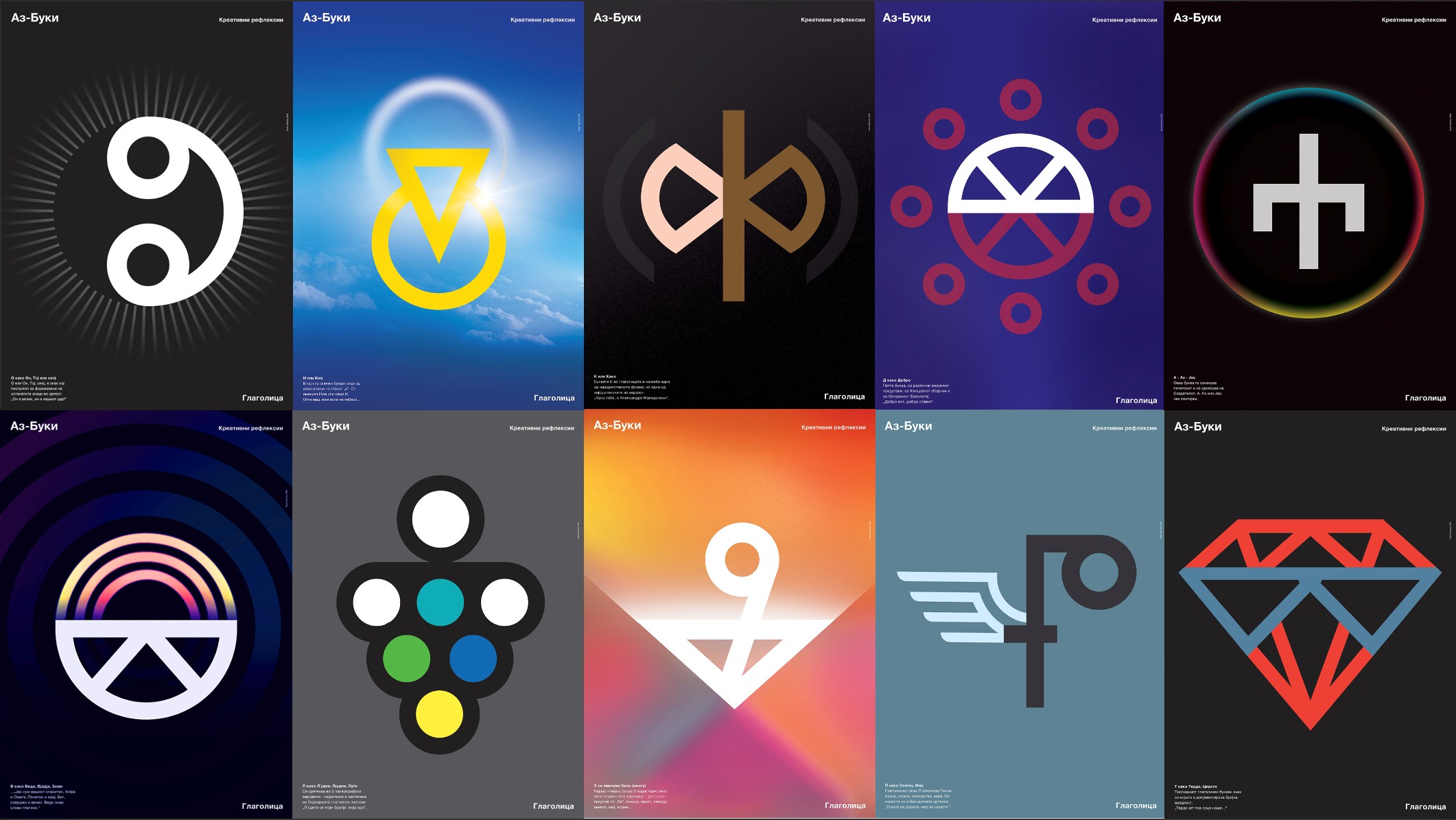

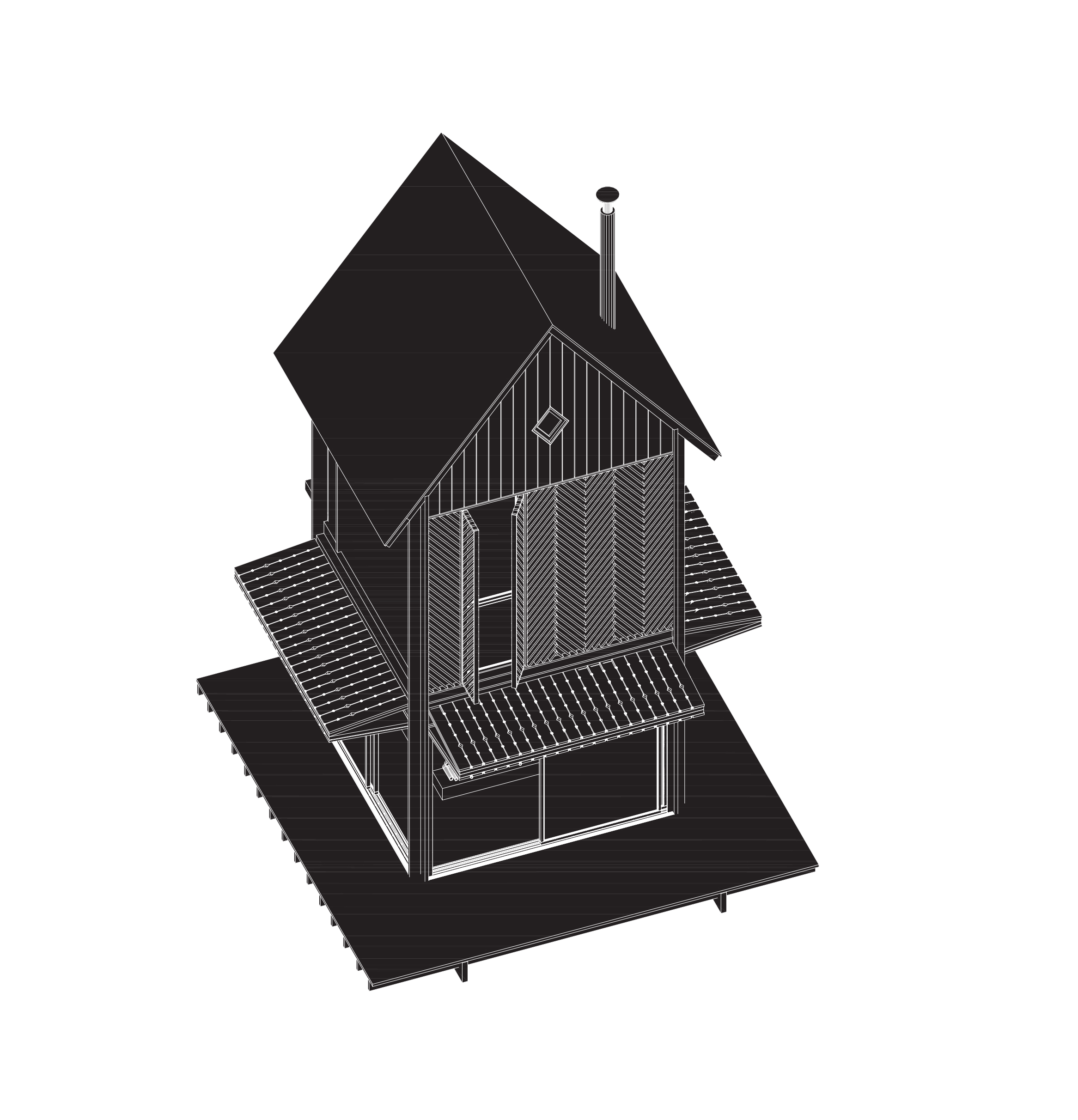

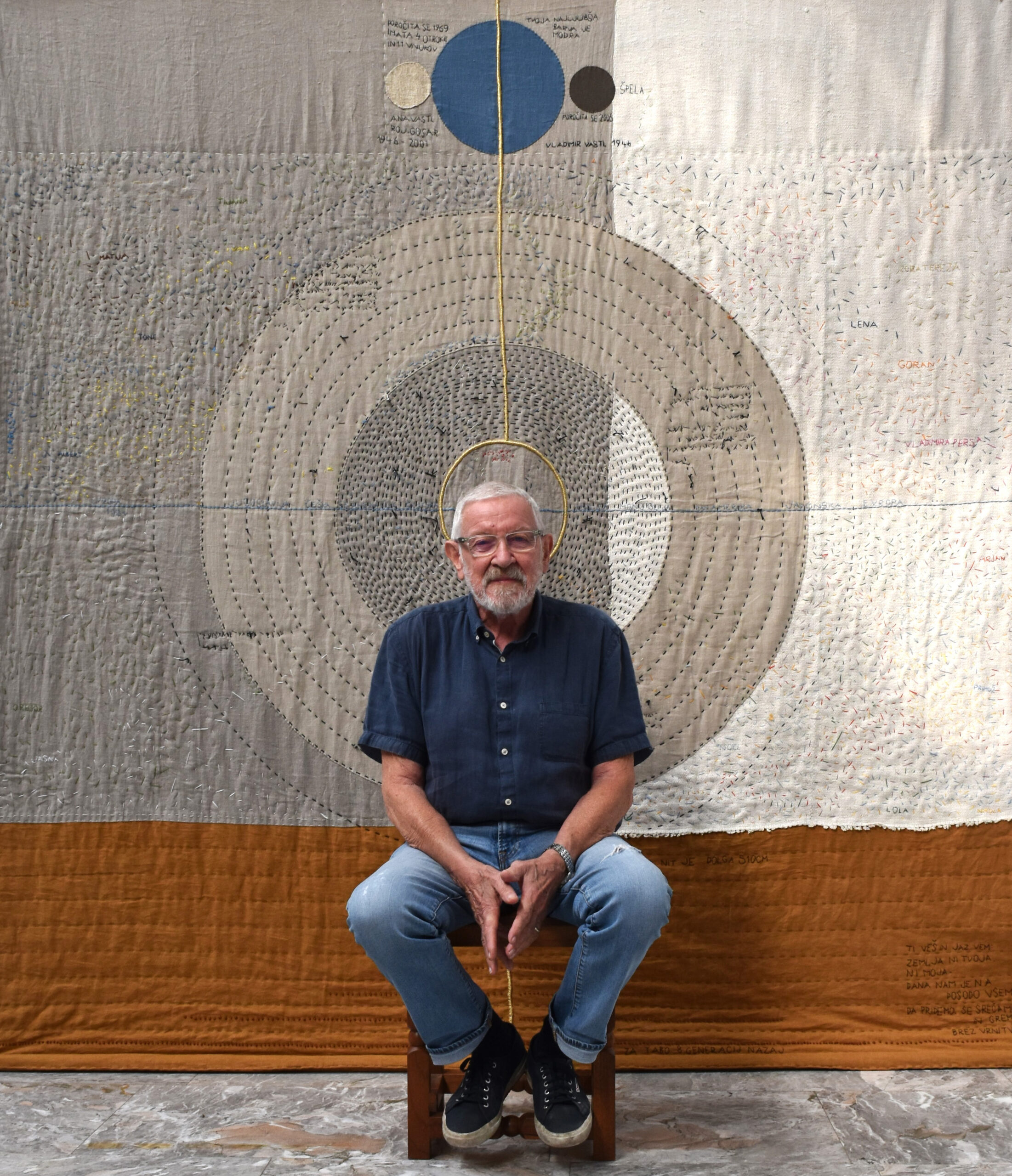

This online Exhibition that represents CEI Member States tends to explore the various forms of interpretation and presentation of traditional cultural heritage (intangible), especially used in the frame of industrial design in the CEI Region. The overall aim of the exhibition is to bring together cultural heritage elements from the CEI Member States (Central European Initiative), in order to show the development from the element to the interpretation and presentation of the intangible cultural heritage in the CEI Region – in pairs. (A. Photo or graphic representation of a selected element of the ICH of the CEI Member States (inscribed on their national lists) and B. Photo – Image of a contemporary object or applied art works (to which the cultural element (A) has been applied).

This Exhibition demonstrates the richness of the different traditions of the CEI Member States, as well as their value and the continuity of such traditions in the CEI Region. The digitization of the national cultural heritage in the Republic of Serbia, as well as in other CEI countries, is a vital issue for our cultural policies, primarily considering the preservation of the identity of our cultural and historical communities and indirectly the identity of the CEI Member States and the CEI Region.

The Republic of Serbia is actively promoting the protection of its tangible and intangible cultural heritage, especially through cooperation with international organizations such as UNESCO, the Council of Europe, ICOM, ICOMOS, etc., as well as on a bilateral basis with the CEI Member States and cooperation within the Central European Initiative provides a good opportunity for this continuity.